Truth, Capitalism, and Documentary Storytelling in Ruth Ozeki’s My Year of Meats

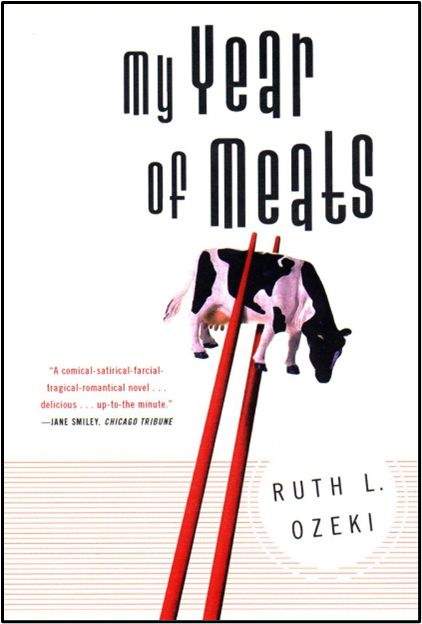

Figure 1. Book cover of Ruth Ozeki’s novel My Year of Meats (1998)

My Year of Meats is Ruth Ozeki’s debut novel and the winner of the Kiriyama Pacific Rim Award in 1998. The novel follows the lives of two women over the course of a single year: American documentary filmmaker Jane Takagi-Little and Japanese housewife and part-time copywriter Akiko Ueno. Initially their lives unfold in parallel chapters but eventually intersect in startling ways due to Jane’s boss being Akiko’s husband and both women struggling with fertility. The novel is a feminist critique of the cultural intersection of capitalism, television, and meat (its production, advertising, and consumption). The novel also illuminates the ethical and ecological problems of using Diethylstilbestrol (DES), a synthetic form of the female hormone estrogen that causes cancer. I sometimes think of the novel as a contemporary version of Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle.

The novel is fictional, but it is based on Ozeki’s observations, experiences, and research, and it includes many references to real historical events. She conducted research on DES and includes references to those scholarly studies in an appendix. References to real events and real people pop up throughout the novel. One example is the murder of Yoshihiro Hattori on Halloween in 1992. Another example is the BSE outbreak of the 1980s-90s, as are Japan’s bans of importing American beef (which began in 2004). These references lend the novel verisimilitude and also contribute to the novel’s discussion of documentary storytelling. The narrator, Jane, reflects on this at the end of the novel: “Half documentarian, half fabulist…Maybe sometimes you have to make things up, to tell truths that alter outcomes” (360). What is permissible in the quest to tell a larger truth and even what constitutes truth itself is a central concern of the novel.

Figure 2. Portrait of Ruth Ozeki

As a documentarian, the narrator Jane is committed to the search for truth and to bringing that truth into the public eye. This professional and ethical commitment is challenged in the novel by her need for gainful employment as the American beef trade export association BEEF-EX—the sponsor of the documentary TV series she created—wants not truth but a carefully crafted and so-called authentic image of American life represented by white, heterosexual, beef-eating, middle-class families in which the father is the breadwinner and the mother a housewife. But due to Jane’s documentarian commitments, authenticity is a contested term within the novel. For the executives at BEEF-EX, authenticity means adhering to a certain preconceived 1950s-era stereotype about American families that was perhaps never an accurate reflection of reality, but which is associated with wholesomeness. For Jane, authenticity is about accurately reflecting the complex reality of American families in all their varied forms.

In my own unpublished work on My Year of Meats, I argue that the novel could be categorized as protest literature: Jane is a reluctant prophet who undergoes a conversion experience, identifies problems and calls our attention to them (and the need for change), and attempts to convert others to the cause. In My Year of Meats, the readers see Jane slowly overcome her uncertainty and timidity to start deviating from the BEEF-EX mandate and challenging the viewpoints of colleagues, gradually awakening to a radical sensibility. Although the novel raises awareness and doubts in the reader, Ozeki’s novel does not make a coherent and sustained criticism of the intersections of patriarchy, feminism, and vegetarianism—unlike, for example, Carol J. Adams’s book The Sexual Politics of Meat. Ozeki doesn’t attempt to convince meat eaters to become vegetarian—but she perhaps does enough in this novel to make such readers begin to doubt and question and want to learn more. After reading this book, some people might at least think about their habits of consumption, and perhaps take action by buying produce and meat from local farmers and by reducing their overall meat consumption.

Additional Resources

Adams, Carol J. The Sexual Politics of Meat. New York: Continuum, 2011. Print.

Luckhurst, Toby. “Yoshihiro Hattori: The door knock that killed a Japanese teenager in US.” BBC, 19 October, 2019. http://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-50063364.

Mason, Jim and Peter Singer. Animal Factories: What Agribusiness Is Doing to the Family Farm, the Environment and Your Health. Three Rivers Press, 1990.

National Cancer Institute. “Diethylstilbestrol (DES) Exposure and Cancer.” https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/hormones/des-fact-sheet.

Raun, A. P. and R. L. Preston. “History of diethylstilbestrol use in cattle.” American Society of Animal Science, 17 September 2001. https://www.asas.org/docs/default-source/midwest/mw2020/publications/raunhist.pdf?sfvrsn=3ac11b67_0.